https://www.sonicextinction.net/

EDT

I WOULD FIRST LIKE TO ACKNOWLEDGE ALL THE INDIVIDUALS THAT WERE RECORDED,

IN THEIR OWN ENVIRONMENT; FOR THIS ARTISTIC ENDEAVOUR. ADVOCATION FOR SIMPLE RITUALS OF ACKNOWLEDGEMENT ARE IMPORTANT TO PREVENT THE DEVELOPMENT OF AN UNDESIRABLE MECHANICAL ATTITUDE TOWARD ONE’S WORK WITH NON-HUMAN ANIMALS.

The idiom ‘You’re going to hear crickets’, often refers to the sound of silence. This is unfortunately already true for Hawaiian Teleogryllus oceanicus, which, by the 1990s had evolved to become silent due to eavesdropping parasitic flies and the loss of a safe habitat. This project will look at the impacts of climate change on orchestral insects, specifically ones found in Toronto, Canada; and how their songs may evolve, or be lost forever. Insects are cold-blooded and therefore cannot regulate their own body temperature. It has been found in many species in the order Orthoptera, that the mechanical movements needed to create sound are directly affected by the ambient temperature. This influence has been found to be so exact, that you can actually count the number of chirps per minute to determine the air temperature.

CRICKET ALARM is a collection of synthetically altered natural field recordings which, following linear mathematical data; begins at the current average temperature and tempo, then is sped up incrementally as the average global temperature rises due to climate change and global warming. Once the chirp frequency reaches 100° F, a level at which these animals could not communicate due to a myriad of threats; the orchestra of chirps fades to silence, signalling the beginning of a mass sonic extinction.

Oecanthus fultoni / SNOWY TREE CRICKET / T = 50 + (N - 92 / 4.7)

Gryllus pennsylvanicus / FALL FIELD CRICKET / T = 50 + [(N - 40) / 4]

Orchelimum vulgare / COMMON MEADOW KATYDID / T = 60 + (N - 19 / 3)

T is Temperature in Fahrenheit

N is Number of chirps/minute

︎ The above formulae are expressed in terms of integers to make them easier to remember—

they are not intended to be exact.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

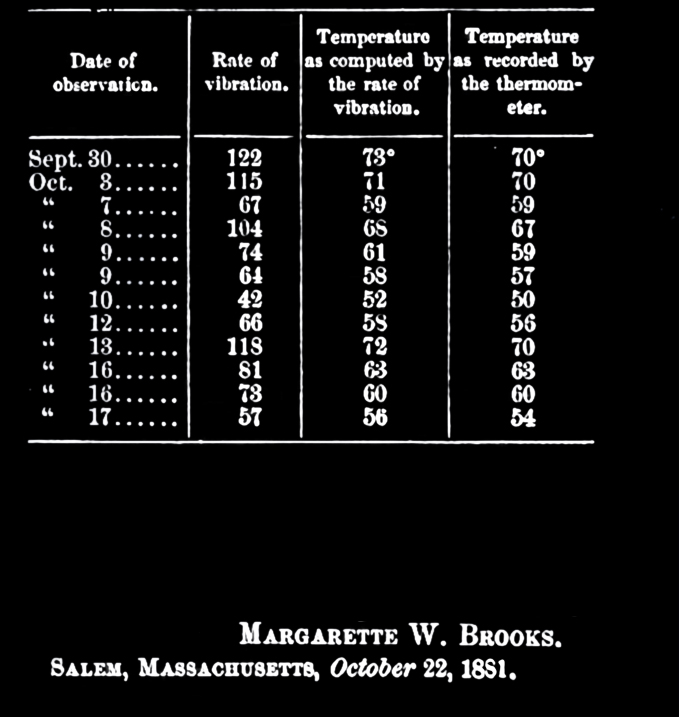

I am using species specific formulae that are elaborations of an equation known as Dolbears Law. In 1897 a man named Amos Dolbear published a brief article titled ‘Cricket as Thermometer’ discussing the relationship between ambient air temperature and cricket chirp frequency.

DOLBEARS LAW: T = 50+[(N-40)/4]

In 1881, fourteen years earlier, a woman named Margarette W. Brooks published a more thorough paper on the same phenomena, including recorded data to support her claim. Her formula, which was republished the following year in Scientific American, expanding her audience, and most likely seen by Dolbear; is the same as Dolbear claimed to have formulated. While Brooks pioneeared this discussion, it is Dolbear’s name that has continued in perpetuity.

︎ This project is an artistic simulation, for more information on this topic:

Allard, H. A. “Changing the Chirp-Rate of the Snowy Tree Cricket Oecanthus Niveus with Air Currents.” Science 72, no. 1866 (1930): 347–49. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1655888.

Edes, Robert T. “Relation of the Chirping of the Tree Cricket (Oecanthus Niveus) to Temperature.” The American Naturalist 33, no. 396 (1899): 935–38. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2453978.

Guerra, Patrick A., and Glenn K. Morris. “Calling Communication in Meadow Katydids (Orthoptera, Tettigoniidae): Female Preferences for Species-Specific Wingstroke Rates.” Behaviour 139, no. 1 (2002): 23–43. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4535909.

Rayner, Jack G., Will T. Schneider, and Nathan W. Bailey. 2020a. "Can Behaviour Impede Evolution? Persistence of Singing Effort After Morphological Song Loss in Crickets." Biology Letters 16, no. 6 (June): 20190931.

Shaw, Kenneth C. “An Analysis of the Phonoresponse of Males of the True Katydid, Pterophylla Camellifolia (Fabricius) (Orthoptera: Tettigoniidae).” Behaviour 31, no. 3/4 (1968): 203–60. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4533229.

Zuk, Marlene, John T. Rotenberry, and Leigh W. Simmons. “Calling Songs of Field Crickets (Teleogryllus Oceanicus) With and Without Phonotactic Parasitoid Infection.” Evolution 52, no. 1 (1998): 166–71. https://doi.org/10.2307/2410931.